Interview with Giovanna Silva, Humboldt Books

Ein Schriftsteller und zwei Fotografen unterwegs durch die Wüste in das Unbekannte. Ihr Ziel: das Buch dieser Reise. Giovanna Silva, Fotografin und Verlegerin von Humboldt Books, erzählt von ihrem Verlag und der Entstehung von Absolutely Nothing: einer Geschichte von Desorientierung und der Dekonstruktion von Zeit und Sprache. Eine literarische und visuelle Fantasie als romanhafte Reiseerzählung.

Clui is the name of a nonprofit organization formed in order to pursue the research on artificial landscape and its interpretation. The acronym stands for Center for Land Use Interpretation, where Giovanna Silva, Giorgio Vasta and Ramak Fazel met as to determine the stopovers of their journey across forsaken deserts and cities. Fully rapt by Google Earth, paper maps and recommended addresses, Giorgio started leafing through books on the shelves. One copy especially captivated him: its title is Overlook and it contains a particular picture of a road gradually disappearing in a desert with only one sign standing on the horizon: Absolutely Nothing – Next 22 miles. The absence of hope alongside those 22 miles, the idea that on the contrary it might exist, waiting for someone to perceive it, as well as the concept of complete vacuity enclosed in a determined space, is what attracted him the most. He then resolved to locate that precise sign once he’s undertaken the journey. However, whenever he encountered one of those yellow rhombus-shaped signs on the way, his hopes ineluctably got disenchanted.

The entire book, which alternates the narration of the chronologically deconstructed journey with parenthetical elements about the future, as well as dialogues, Skype conversations and retrospective thoughts, is structured precisely according to these tensions. It all results in a product made of multiple points of view, with different types of writing, documentation pictures, comic strips from Peanuts and a special section exclusively devoted to visual reports. American deserts through tales of the evanescent.

LZ

I shall begin this interview with a tale from Absolutely Nothing, referring to the journey across the American deserts as to better outline the research behind my work and the questions I want to ask you, all with focus on the concept of journey and the language which better fits to your report. Your publishing company Humboldt Books seems to place substantial importance on the language and on the correct narrative form. All the while not only many interesting collaborations between writers and photographers have emerged, but also new opportunities for artists who re-elaborated their experiences by converting them into words rather than presenting images. Furthermore, we can clearly distinguish your particular attention to the individual and their attitudes, the observing eye that extrapolates the most suitable narrative form to represent their experience. Apart from a brief presentation about the essence of Humboldt Books, I‘d like you to tell me something about such a transformation: how much do travel stories change according to the form through which they’ve been conveyed, be they logbooks, visual sequences or simple narrations of one’s past? Which thoughts did you come up with and which method did you adopt in order to create the collage of experiences and faces represented by Absolutely Nothing?

GS

I’d like to answer this question starting from the very end. Absolutely Nothing was the culmination, the last issue from a series of books involving a photographer and a writer in a common journey. Travel stories by definition belong to the non-fiction genre. It was very interesting for me, both as publisher and as mere reader, to see how the writing style and the issue of travel changed from one book to another. We began with a very intimate and sentimental diary by Vincenzo Latronico on the track of his maternal family in Ethiopia, and then we concentrated on a more traditional and literary story about a trip across Greece hand in hand with the descriptions by Dino Baldi, who wanted to recall the journey of Pausanias. Eventually, the whole thing culminated in a narration which we ought to call novel, that turned me, Silva, and the photographer Ramak into real characters. It converted our features and changed our traits, making Silva look like a cross between Ludwig von Drake and the Pythia, and Ramak falling somewhere between George Clooney and Peter Sellers in The Party. The narration itself loses its documentary features and gains the qualities of a proper fiction. Paradoxically, what seems to be invented turns out to be real and what appears as trivial is in fact a mere writing desire.

LZ

As soon as the narration starts, it’s also the beginning of something going beyond everyday life, as if the reality were transcended elsewhere. This happens both in written and in visual stories, with stress layed on the endeavor to convey a journey’s idea. When did you first feel the need to tell and share stories? By sharing meaning a communion with both your travelling companions, who are authors themselves, and a wider audience.

GS

I’ve been working as a photographer in editorial offices for 8 years, initially for Domus and then for Abitare – technically I’m a failed architect. The most interesting experience I can recall now relates to my work with a writer with whom I tried to see how the same architectonic object, the same city, could be described in disparate manners depending on the means of our visual conception. At the age of thirty I went through a crisis and decided I would bring back together my two passions for books and travelling. Sharing experiences with the authors matters a lot since it’s the only way for me to never stop learning. But the audience has its importance too, because feedback is the sole parameter for understanding whether I’m doing my job well.

LZ

The desert described by you, Giorgio Vasta and Ramak Fazel, has quite the same significance as a feeling of bewilderment, as a loss of coordinates of a foreigner in a foreign place, which however is perfectly familiar in the unconscious. It exemplifies the traveler’s experience as an anthropologist in the broad sense. You carefully leaned towards an alien reality with your own means and attempted to create a new form of representation without neglecting neither the doubt nor its fragmentary nature. While I was reading your stories, I couldn‘t help but get captivated by a continuously hovering question about time and space perceived as fade glimmers sliding back and forth, up and down.

GS

I don’t know whether my answer perfectly matches your question, but I can say that Absolutely Nothing really was a unique experience. And, nor let there be any sentimentalism, Giorgio, Ramak and I would never leave each other. The temporal displacement you underlie is due to multiple factors, not at least regarding the travel‘s practicality. The journey was undertaken in 2013 and the book was released in 2016. During these three years our lives have changed a lot, but I’d also like to tell you about something personal. Throughout the journey, which lasted 20 days, we spent an average of 14 hours together in the same car and neither of us said a word about one‘s life. What mattered was the journey. Our life, our ordinary life, had been left overseas. As soon as we came back home we truly got to know each other. The life of the other became part of oneself and we gave a retroactive value to all those behaviors we shared in the desert. Spike, the book’s fourth character, his incursions, and these temporal displacements, they’re all about that shared ego which somehow only the three of us are able to perceive. For this reason I compared the book with a novel, rather than with a simple travel report.

LZ

Going away and stepping out into the unknown are key dynamics in the world of journeys, but at the same time forms of travel narratives tend to preserve a certain canon, a style recalling adventures, everyday chronicles, explorer’s studies and field researches. The travel stories narrated here are individual and show us both author’s and character’s fears and weaknesses; they can be classified as meta-books which make us ponder on the sense of estrangement itself, with no prescribed interpretations for us, aiming at an innocent way to look at the world. May we say that Humboldt Books recovers and questions new tensions and stimuli for travel stories?

GS

I really hope so! I didn’t make up anything, travel stories have existed not only since the ages of Alexander von Humboldt, and up until 50 years ago, maybe less, the idea of having a writer and a photographer involved in a journey was something ordinary. What I’m trying to do is to revive travel stories in times where journeys can be organized online and the idea of adventure unfortunately is only a remote memory. What’s left of the uncertainty and of the journey itself is something I’m trying to find out.

LZ

The protagonists of this journey are a writer, a photographer and your guide, but in fact it’s the writer who chooses their destination. Could you tell me why?

GS

In the series of books, texts should have prevailed over images. We usually choose a writer and he chooses a country, and then, depending on the country and on the journey elected, we select a photographer who, from time to time, is considered more apt to portray the country concerned. However, we are inverting such inclination. We’re currently working on a book about Palermo, the native city of Giorgio Vasta, with photos by Ramak Fazel. From Absolutely nothing to Absolutely everything. Here the leading role will be played by photography and Palermo will be portrayed by Giorgio through Ramak’s eyes – did I already mention that we would never leave each other?

LZ

Just to conclude our interview I ask you to share a thought about the person after whom the publishing company is named: Alexander von Humboldt. When did you first come across his works and what’s the most fruitful inspiration that you have gathered from him?

GS

After studying architecture I began to attend anthropology classes and I took an exam about Alexander von Humboldt. As soon as I came across one of his statements – which I later had the privilege of placing on the back cover of a volume about his works published by our office – I couldn’t help putting myself in his shoes, I wanted to identify myself with him. He’s a humanly complex figure who squandered a fortune to follow his adventurous dreams, who risked his life for science’s sake, who neglected everything for knowledge. In other words, an obsessive man, a legend.

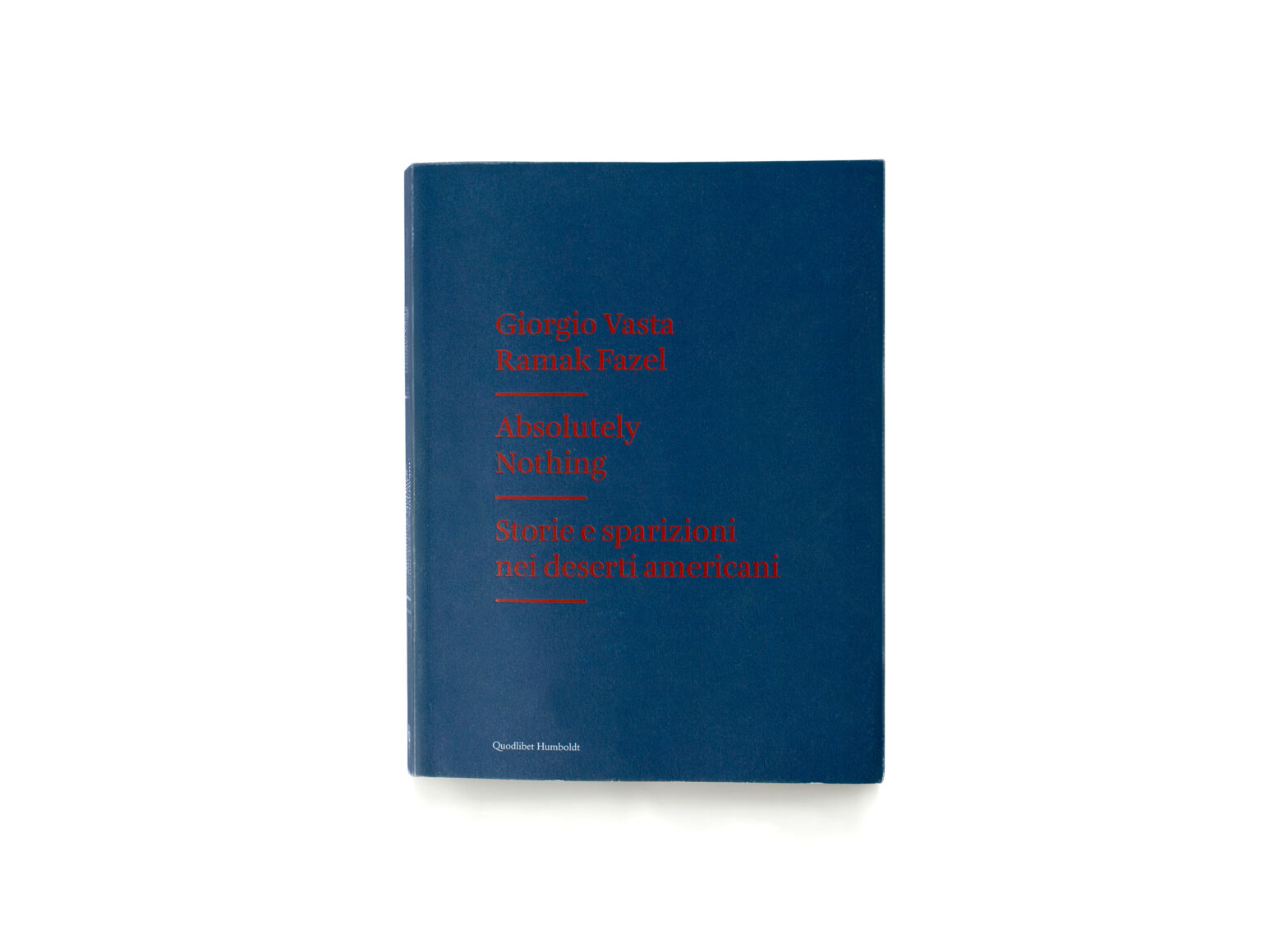

Absolutely Nothing, Humboldt Books 2016, 165 x 220 mm, Fotografie und Text, 296 S.